According to the 2021 status report on IT security in Germany, 394,000 new malware variants are created every day. In order to protect oneself as best as possible against this, regular patching and the installation of updates is one of the main tasks of an IT manager. But how did the patches, updates and upgrades known today come about in the first place, and why should you fix what isn’t broken in the first place? This article will provide you with the information.

Due to their similarity, these three terms are often confused.

However, there are clear differences, which we have summarized for you here:

PATCH

In short, a patch represents a bug fix to close a vulnerability.

UPDATE

An update, on the other hand, brings a new, smaller function update and can thus provide new features or improve older ones.

UPGRADE

In an upgrade, a new, revised version is installed.

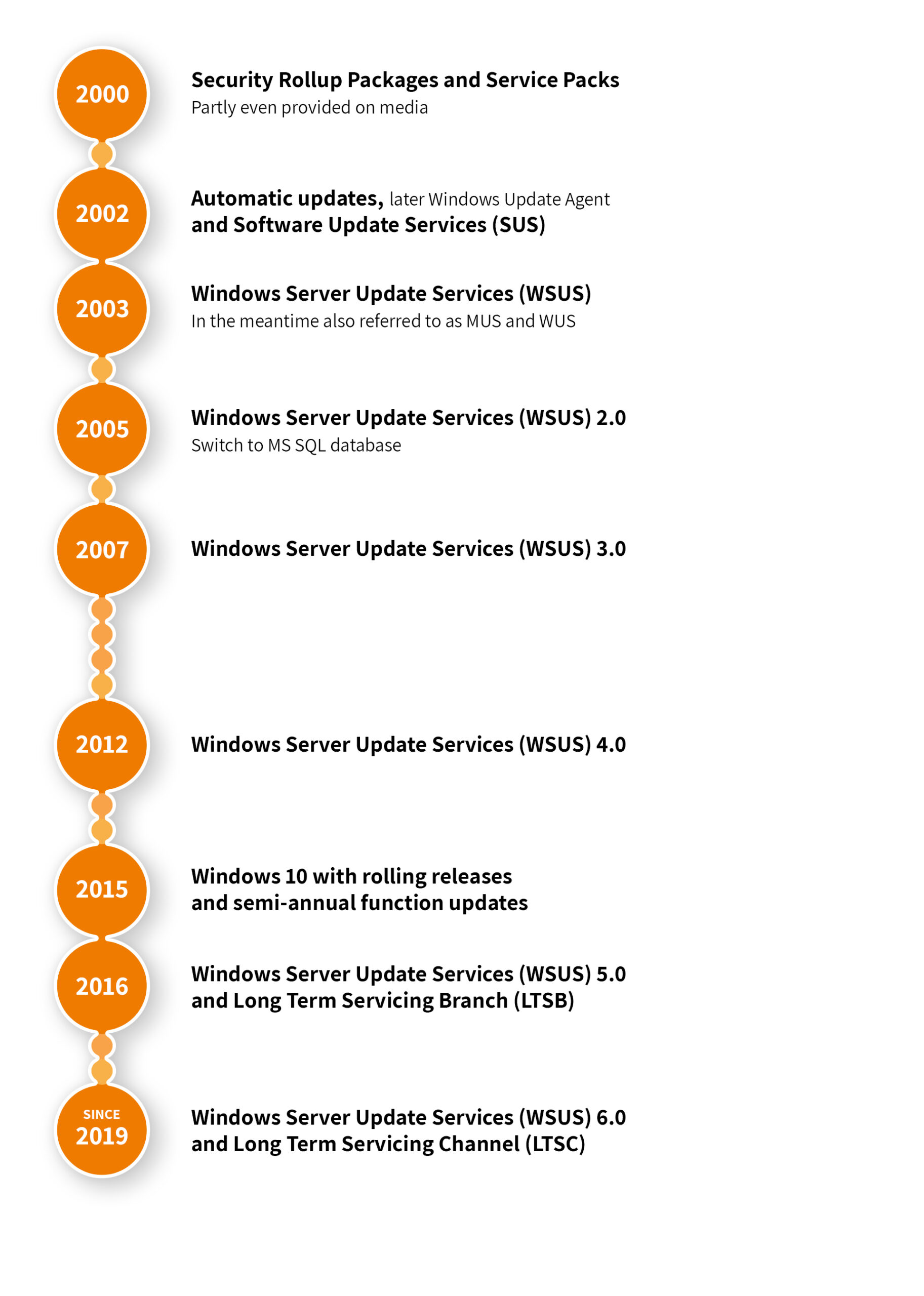

Microsoft Update services have evolved over time as follows:

Before Windows 2000 SP3, updates were organized by Microsoft in so-called Security Rollup Packages and Service Packs [1]. Thus, various bugs were fixed and new functions introduced in longer, more or less irregular intervals, which corresponded more to an extensive upgrade than a dedicated patch for a concrete problem. In the absence of widespread broadband coverage, these were sometimes even made available on media, e. g. also via magazine CDs of well-known computer magazines. With the feature of the “automatic updates” (later Windows Update Agent) Microsoft offered since 2002 a possibility to provide and install individual updates automatically in the background. Parallel with the SUS (Software Update Services) and the successor WSUS (Windows Server Update Services – in the meantime also MUS and WUS [2]), which is contained since Windows Server 2003, a service was made available to provide and release updates locally in the company. Since then, many administrators are looking forward to the second Tuesday of the month, the so-called “Patch Tuesday”, when Microsoft provides new updates. Also, Microsoft currently refers to patches that are unplanned, necessary outside of the regular rhythm and are released at short notice as out-of-band updates (OOB).

Windows 10 was supposed to be the “last” version of Windows, which remained up to date by means of so-called rolling releases and semi-annual function updates (04 April and 09 September, later H1 and H2) [3]). Patches for security-relevant updates or for bug fixing continued to be provided within these releases on Patch Tuesday. In order to be able to extend or even suspend the cycles for a mandatory update in enterprise environments, the Long-Term Servicing Branch (LTSB) (later Long-Term Servicing Channel (LTSC)) was introduced alongside, which provides enterprise and IoT enterprise versions in 2-3 year intervals. During the transition from LTSB to LTSC, the channels for private users, Current Branch (CB), and business customers, Current Branch for Business (CBB), were primarily combined into a Semi-Annual Channel (SAC).

To further speed up and simplify the update process, other methodologies such as Cumulative Updates ([4] CCU – combine all updates up to a certain level into one common update) and Servicing Stack Updates (SSU – includes the main components for the update mechanism and Windows deployment) have been introduced.

However, not only the operating systems (here using Microsoft Windows as an example), but also other installed applications were increasingly supplied by their manufacturers with bug fixes (patches) or smaller function updates. Completely revised versions, so-called upgrades, sometimes bring new prerequisites and dependencies with them and can, for example, require completely new hardware in production (cf. TPM-2.0 for Windows 11), which has a significantly greater impact.

To simplify readability, the term update is often used as a synonym in the following.

Updates not only bring bug fixes, e. g. for memory leaks or to close vulnerabilities, but can also bring new features and technologies if necessary, such as the Windows Firewall with XP SP2 [5]. To secure systems, other mechanisms have been developed over time such as write protection filters, sandboxing, system hardening, application whitelisting, execution restrictions, virtual patching, and several others. These techniques can mitigate or even prevent the exploitation of existing vulnerabilities if necessary, but they only address the symptoms and not the root cause. Therefore, depending on the area of application, these options are often used for rapid implementation until an update is made available by the manufacturer or as a last resort for legacy systems that are no longer supported.

Here you can learn more about the pros and cons of virtual patching and when it makes sense to contain vulnerabilities using this principle.

In IT environments, two weeks have often proven to be a good measure for releasing updates. When Microsoft provides new updates on Patch Tuesday, they leave the first (un)voluntary tests to the home users and wait for the results. If the search for the corresponding KB entries doesn’t bring a flood of forum posts, the courageous administrator can assume that he can release this update on the first systems without having to expect dramatic surprises. However, depending on the installed hardware, installed components and other software, other conditions may arise that make an update necessary or not, or even possibly lead to another superseeded (replaced) or superseeding (replacing) update. And in this combination, what previously worked hundreds of times can then go wrong on individual devices. If this happens in a home environment it is very annoying, in an office it hinders work, but in production it can have fatal consequences up to production downtime.

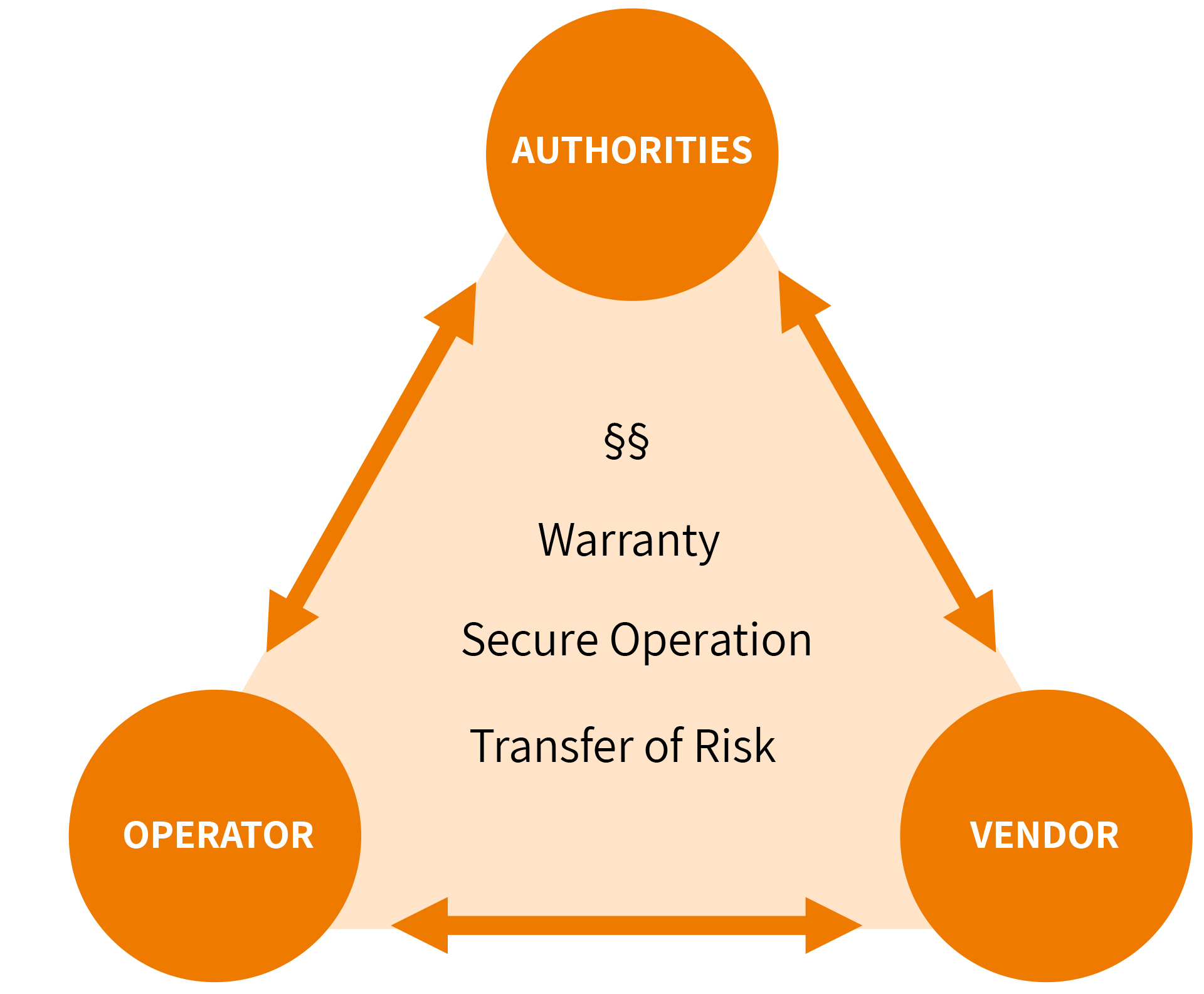

Independently of the company’s decision between production downtime due to attack or problems possibly caused by updates, there are also other requirements imposed by authorities that can affect both operators and manufacturers (keywords KRITIS, IT-SIG 2.0, …) and may require action even in contrast to their own assessment.

The triangle of OT stakeholders shows that the interaction and interdependencies between manufacturers, plant operators and authorities is becoming increasingly important:

In 2015, Microsoft still spoke of the “last” Windows version with the introduction of Windows 10, which should only be further developed with functional updates. In the meantime, Windows 11 has been officially released, the support of updates for Windows 10 from 2025 has been discontinued [6] and there are also exciting developments in the architecture (keyword: ARM and x64 emulation).

We will continue to monitor for you how Microsoft’s update strategies develop in the future and support you in simple and efficient testing, distribution and installation. And if you want to know which three metrics can help you classify Microsoft updates, we recommend you take a look at the video below:

Sounds interesting? Here you can download the summary as a PDF free of charge.

[2] https://www.msxfaq.de/windows/update.htm

[3] https://docs.microsoft.com/de-de/windows/release-health/release-information

[4] https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/deployment/update/servicing-stack-updates

[5] https://petri.com/windows-xp-sp2-firewall

[6] https://docs.microsoft.com/de-de/lifecycle/end-of-support/end-of-support-2025

Here you can learn more about our company and our expertise as a pioneer and market leader.

Would you like to learn more? Do not hesitate to contact us, we will be happy to help you.